(Image description: A view from above shows two women sitting at an office desk, looking at a laptop together. The woman on the right is a wheelchair user.)

In the journey toward creating a truly inclusive society, one important aspect is understanding disability etiquette. Disability etiquette encompasses a set of guidelines and practices that promote dignity, accessibility, and inclusivity in our interactions with people of all abilities. This goes beyond mere politeness; it is about fostering genuine respect, understanding, and equal treatment for individuals with disabilities.

So why is disability etiquette important? First and foremost, understanding disability etiquette is crucial for promoting equal opportunities and breaking down barriers faced by individuals with disabilities. In many cases, people with disabilities encounter social, physical, and institutional barriers that hinder their full participation in various aspects of life, including education, employment, and social activities. By understanding and practicing disability etiquette, we can help dismantle these barriers and create environments where everyone feels valued and respected. In addition, disability etiquette promotes social equality and respect. When we relate to each other as humans with unique skills and qualities, we avoid reinforcing stigmas and stereotypes based on perceived differences. This makes for a more integrated, inclusive and socially diverse community.

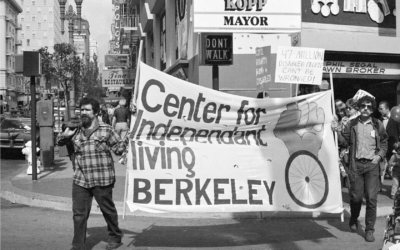

CPWD and City of Boulder

On Thursday, February 8, 2024 the Center for People With Disabilities and the City of Boulder partnered up to offer a comprehensive training program on disability etiquette designed by CPWD to equip City of Boulder staff with the knowledge and tools needed to foster inclusivity and accessibility. This work is in direct relation to the city’s equity efforts and commitment in continuing to address institutional and structural inequities that impact our community. By providing ongoing learning, the city hopes staff feel equipped and prepared to serve community members with necessary supports and services. The training covered several of the key topics and principles to educate on the importance of and how to practice disability etiquette. The program was facilitated by Craig Towler, Community Organizer at CPWD.

Key Principles of Disability Etiquette

There are several key principles that underpin disability etiquette covered in the training:

Understanding Ableism

A woman in wheelchair is waiting before a set of stairs unable to move her wheelchair.

We must first understand what ableism is in order to notice when it is happening and then take the steps to change the problem. Ableism is the discrimination of and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that typical abilities are superior. Ableism tends to view people with disabilities as needing “fixing.” Much like racism and classism, ableism classifies an entire group of people as being inferior, propagating harmful stereotypes and generalizations.

Individual ableism feeds systemic ableism. Systemic ableism includes the physical barriers, policies, laws, regulations, and practices that exclude people with disabilities from full participation and equal opportunities. Examples include lack of accessibility to stores and public places, lack of accommodations in schools and in the workplace, limited or no health coverage for pre-existing conditions, and more. Undoing systemic ableism requires policy change at all levels of government – city, county, state, federal.

Respect and Dignity: Treat individuals with disabilities with the same respect and dignity that you would afford anyone else. Avoid making assumptions or judgments based on stereotypes or misconceptions about disabilities. Oftentimes, people with disabilities experience what are called “ableist microaggressions.” These are subtle, possibly unintentional, discriminations against individuals based on their disabilities. These can be statements, actions, incidents or exclusions. Some examples include:

- Someone telling a person with a disability they will pray for them

- Telling someone they don’t look disabled

- Congratulating someone with a disability on doing something not worth congratulating them on, or that in the viewer’s mind, is typically only achievable by a non-disabled person

Craig, a wheelchair user, gave an example in the training about how within one week, three different people gave him a compliment on how well he was using his wheelchair. “Which was very nice,” he acknowledged, “but it would be the same thing as me saying, ‘Oh wow, you’re really good at walking!’”

Ask Before Offering Assistance: If you encounter someone who appears to need assistance, ask them first before offering help. Respect their autonomy and allow them to communicate their needs and preferences.

In the training, Craig offered an example of how this has happened to him in the past. He often will go out on the local creek path, which has an uphill angle, to get a workout by using his wheelchair on the incline. He shared that people have in the past, without even asking, come up behind him and began pushing him up the hill. Though their intention was to be helpful, the assumption that he was in need of help was based in an ableist belief.

Accessible Communication: Be mindful of different communication needs and preferences. Speak clearly and directly to the individual, and if necessary, ask how you can best communicate with them. Avoid making assumptions about someone’s ability to understand or respond. Active listening is a large part of effective communication. Ask follow-up questions if you don’t understand.

Person-First Language: Use person-first language that emphasizes the person rather than the disability. This helps to affirm the individual’s identity and humanity beyond their disability. For example, we are the Center for People With Disabilities, not the Center for Disabled People.

Some outdated language to avoid using is:

- “Disabled person” – instead say “a person with a disability.”

- “Low-functioning” – instead say “greater support needs.”

- “Normal” or “healthy person” – instead say “a person without a disability.”

- “Non-verbal” – instead say “a person who communicates without using words.”

- “He or she has a problem with…” – instead say “he or she needs” or “he or she uses.”

- “Learning-disabled” – instead say “they have a learning disability.”

- “Retarded”, “slow”, “simple”, “moronic”, “defective”, or “special person” – instead say “person with an intellectual or cognitive disability.”

Image description: Two women sit at a table, speaking in sign language. One woman has her back to the camera. She has shoulder length blond hair and a plaid grey shirt. The other woman has long brown hair and a polka dot shirt. Behind them are a vase of flowers and a book shelf.

During the training, many of the City of Boulder employees asked important and probing questions. One participant pointed out that she has friends who are hearing-impaired. Her friends prefer they be called “deaf” or “hard-of-hearing,” which many people frown upon. Craig pointed out that personal preference on how one wishes to be identified always takes precedence. This returns us to the point of accessible communication, and always asking questions and using active listening to understand another person.

Respect Personal Space and Boundaries: Just as you would with anyone else, respect the personal space and boundaries of individuals with disabilities. Avoid touching mobility aids or service animals without permission, and be mindful of physical barriers that may impede accessibility. Don’t organize or move personal belongings without asking first. Even items like rubber bands, tape or stickers may be tactile markers that serve a purpose for them. And never assume they need help, always ask first.

Be Patient and Flexible: Understand that individuals with disabilities may require additional time or accommodations to fully participate in activities or conversations. Be patient, flexible, and willing to make adjustments as needed to ensure inclusivity.

Professional Spaces: Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, people with disabilities can expect reasonable accommodations to make their job accessible and successful. These accommodations should not be viewed as special treatment, but adjustments that help everyone. Some of the accommodations are:

- Physical accommodations:

- Installing a ramp or modifying a restroom

- Modifying the layout of a workspace

- Accessible and assistive technologies

- Ensuring computer software is accessible

- Providing screen reader software

- Using videophones to facilitate communications with colleagues who are deaf

- Accessible communications

- Providing sign language interpreters or closed captioning at meetings and events

- Making materials available in Braille or large print

- Making sure websites are accessible. (For more information on this, read this previous CPWD article.)

- Policy enhancements

- Modifying a policy to allow a service animal in a business setting

- Adjusting work schedules so employees with chronic medical conditions can go to medical appointments and complete their work at alternate times or locations

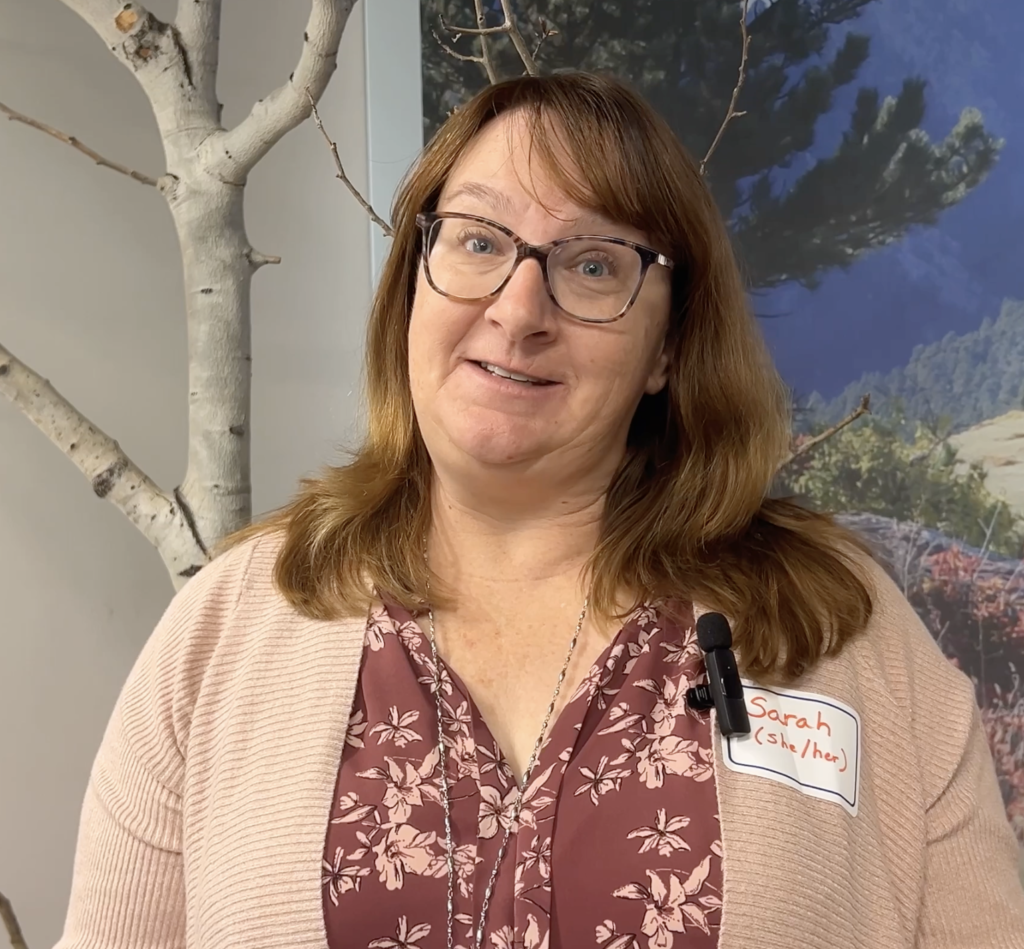

Sarah Huntley, the director of Communications and Engagement. She has shoulder length brown hair, glasses, and is wearing a brown floral shirt with a tan cardigan.

Sarah Huntley is the director of Communications and Engagement for the City of Boulder. She attended the Disability Etiquette 101 training.

“We have a responsibility and desire to serve everyone in our community,” she said after the training. “We learned today just how many people in our community have a disability. Some [disabilities] are visible and some are not visible. It’s very important that we be able to adjust our services and programs as well as our facilities so everyone feels welcome.”

In closing, we need to continue this education in our communities and continue to educate ourselves so we can reduce discrimination (intentional or not), and increase respectful and effective treatment of people with disabilities in our society. Understanding disability etiquette is not only a matter of courtesy; it is a fundamental aspect of creating an inclusive and accessible society. By adhering to principles of respect, empathy, and accessibility, we can build environments where individuals of all abilities feel valued, supported, and empowered to participate fully in society. By embracing disability etiquette, we take a significant step toward realizing the promise of equality and inclusion for all.