Over the past several weeks, we have talked about disability rights, brain injury, and highlighted some key figures in the Independent Living Movement from history and today. In this last week of March 2023, we want to share about intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) – the dark history of how people with IDD have been treated in the past, some of the triumphs that have led to more human and equitable treatment, and where we are today when it comes to independence for people with IDD.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan declared March to be Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Awareness month. Reagan urged people to provide individuals with developmental disabilities “the encouragement and opportunities they need to lead productive lives and to achieve their full potential.” This was a great step forward for a population of people with disabilities that have had an extremely difficult history.

There are more than 7 million people with IDD in the US. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), developmental disabilities are defined as impairments in physical, learning, language, or behavior areas, and include:

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Cerebral palsy

- Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- Learning or intellectual disabilities

- Hearing loss

- Vision impairment

- Other developmental delays

A Dark History

From the dark past, progress forward has been a series of forward and backward steps, not a straight line. It has only been in the last few decades that we have seen people with IDD receive the dignity and respect they deserve to lead happy lives as members of society. Historically, they have faced inhumane forms of ableism – a way of thinking about someone with a disability as different and inferior to self and others.

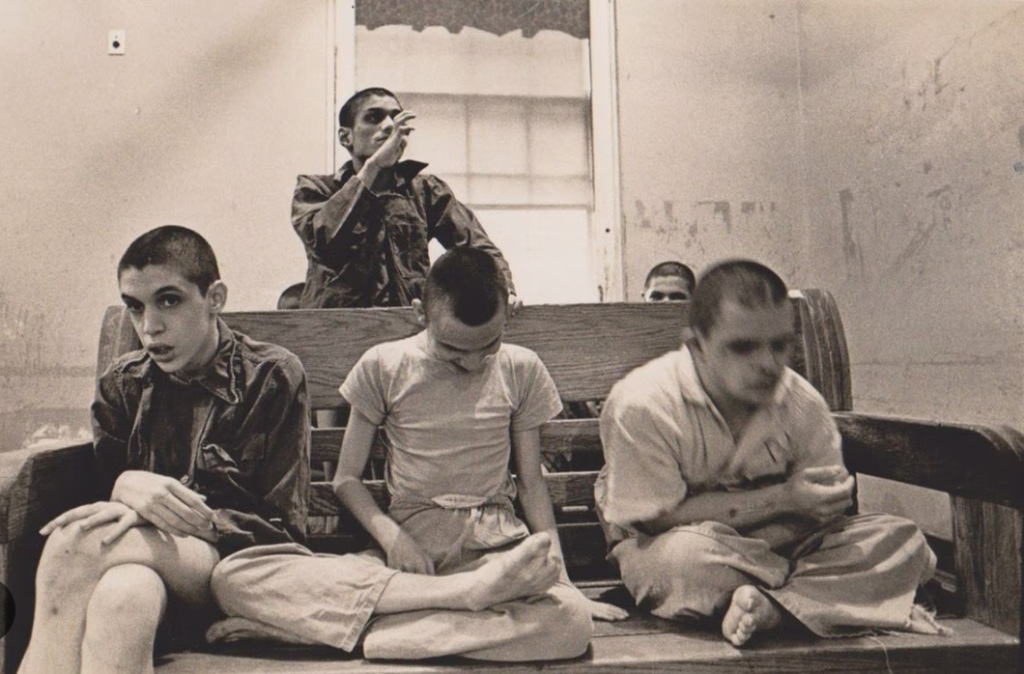

Children in the Willowbrook Institute. Image description: the photo is black and white. There are four boys. three are sitting on a bench, one is standing behind the bench. They all have buzz cuts. The boy on the far left has one leg crossed over the other and is looking off into the distance. H is wearing a dark shirt and shorts. His knees have visible blemishes. The boy next to him to the right is looking down into his lap. His legs are crossed in front of him. He is wearing a white t-shirt and white pants. The boy next to him is blurred in the image as if he was rocking forward quickly. He is also wearing white pants and a white shirt. The boy behind them has his hand in front of his face. He is wearing a dark shirt. The room behind them has a window, and walls with peeling paint. The room looks like it is in disrepair.

For much of recorded history, people with IDD, sadly, were abandoned, institutionalized, and even euthanized. Before the 17th century, babies with IDD were often abandoned and left to die and were considered less than human. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, people with IDD were called “idiots,” and handed over to the government which would place them with caregivers. In 1769, the Virginia legislature passed an “act to make provision for the support and maintenance of ideots, lunaticks, and other persons of unsound minds,” which supported the general sentiment of the time that people with IDD needed to be segregated and out of sight. Large institutions were built to house people with IDD, and most spent their entire lives institutionalized, locked up, and living under horrid and inhumane conditions.

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that the perception of people with IDD began to subtly shift from sub-human and outcast towards slightly more dignity and respect. In Europe, a growing philosophical interest in education and human nature emerged. One propagator of this movement was Jean Marc-Gaspard Itard, who developed a systematic training program for educating people with severe IDD. People suddenly recognized that people with IDD were capable of more than had been assumed. The success of his program was brought to the United States where it was adopted by many of the institutions that housed people with IDD. In 1849, the Massachusetts School for Idiotic Children and Youth was built.

Early IDD education focused more on vocational training than academics and fostered a shift away from the less-than-human perspective of “idiocy” to a more humane perspective of people with IDD. However, the vocational skills they were taught were often used to maintain the institutions themselves, and not improve the lives of the people who lived in them. People with IDD continued to be segregated from society.

Beginning in the mid-19th century, the U.S. experienced a great influx of immigrants. This immigration wave created a rapid shift in the population and economy, leading to political and social tensions. A loud voice among U.S. citizens proclaimed that society was in decay and that many immigrants were people who were “genetically unfit,” such as people with IDD and people of other ethnicities. As a result, the politicians and lawmakers of the time simultaneously passed restrictive immigration laws and laws mandating forced sterilization. In 1911, Woodrow Wilson, then the governor of New Jersey, passed a law that permitted the sterilization of people deemed “unfit.” People with IDD were specifically targeted. By 1927, 33 states had adopted forced sterilization laws.

Though the laws remained, the philosophy of forced sterilization based on eugenics (the science of managing human reproduction to yield more favorable characteristics) began to lose popularity after World War II. The world had witnessed the horrors of the holocaust, that operated under the same philosophic principles of controlling generational genetics through sterilization practices. Even so, forced sterilization and other laws resulting in the discrimination of people with IDD remained in place until the early 2000s. For example, Colorado’s healthcare system allowed for the unregulated practice of forced sterilization during much of the 20th century. Colorado passed a forced sterilization law in 1981. The Colorado Supreme Court decreed that a district court could authorize the sterilization of a “mentally retarded person” if enough evidence was given to deem it medically necessary. It wasn’t until 2020 that the Colorado Revised Statutes stated that any person over the age of eighteen with an intellectual or developmental disability has to give informed consent before sterilization. It is estimated that 60,000 people were sterilized under these laws across the country between 1909 – 1960.

The Independent Living Movement

Ed Roberts and Judy Huemann. Image description: The photo is in black and white. Ed Roberts sits on the right in a wheelchair. He wears dark pants and a white shirt. Straps are across his torso in multiple places and his head is resting against a pad. To his left is Judy Huemann. She also sits in a wheelchair. She is wearing glasses with shoulder-length hair. She is wearing a button-down collared shirt and a skirt. She has on knee-high knitted boots. Behind them are several other people, some holding signs that say “rights for disabled”

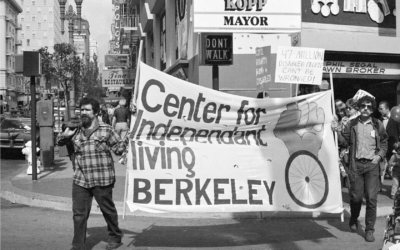

The tides truly began to turn for people with IDD with the birth of the Independent Living Movement. This began when Ed Roberts sued UC Berkeley in 1962 in order to be admitted to the school, as we spoke about in previous articles. He won the lawsuit and was admitted, and proceeded to launch the Disabled Students’ Program (DSP), which fought for access for all people with disabilities to schools and society as a whole. The work of the DSP pushed back against the idea that people with disabilities had to live in institutions and be segregated from society. This included people with IDD, who had not yet been viewed as true members of society.

This movement quickly rippled upward to the highest level of government. Just a few months after Ed Roberts won his suit, President John F. Kennedy, at the urging of his sister Eunice, launched a research panel to study IDD and educational programs called the President’s Panel on Mental Retardation. This panel consisted of 26 leading scientists, physicians, psychologists, and educators. In 1962 they published a report outlining 95 recommendations to improve the lives of people with IDD. From this report, the Community Mental Health Act (CMHA) of 1963 was passed, which provided grants to states in order to build research facilities that could focus on issues related to IDD, establish community-based mental health centers and facilities, and train educators in effective methods for working with people with IDD.

When President Kennedy signed the Act, he declared, “When carried out, reliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation will be supplanted by the open warmth of community concern and capability. Emphasis on prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation will be substituted for desultory interest in confining patients in an institution to wither away.”

President John F. Kennedy signs the President’s Panel into existence. Image description: The photo is in black and white. President Kennedy sits at a desk and is signing a document. He is wearing a dark suit and tie. Standing behind him are dozens of men and women in suits and dresses watching. Behind the crowd of men and women are large windows with paneled drapes.

In other words, this was the presidential declaration that the age of segregating people with IDD to institutions was over. Instead, smaller community programs would be created not only to care for people with IDD but also to help them live to their fullest potential as members of society. Though the initiatives of this act slowed significantly after President Kennedy’s assassination, it marked the beginning of a process that has continued to flourish. At a peak in 1967, 228,843 people with disabilities were in county or state-run facilities. Thanks to the DSP, Kennedy’s initiative, and other forward progress, by 1986 this number had more than halved to 103,296.

In 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which was later renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, was passed. This act finally mandated the free use of public education in nonrestrictive environments and the use of individual education plans for people with IDD. This was a monumental step, allowing people with IDD to access education opportunities that could be personalized to individual capabilities, and also eliminated historical segregation from other students. A far cry from the exploitative “education programs” of the 19th century that used people with IDD as institutional workers, the IDEA empowered individuals, their passions, interests, and capabilities, and their equal place in society. People with IDD were now being given respect, and the opportunity to live to their fullest potential.

In 1990, former president George Bush, Sr. signed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This monumental piece of legislation provided even more access and equality for people with IDD. The ADA makes unlawful discrimination that is based on “(a) a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities; (b) a record of such an impairment; or (c) being regarded as having such an impairment.” This ensures that people with disabilities are no longer pushed to the margins of society, and are given the same rights as all U.S. citizens should have. Equality was finally written into law and gave people with IDD the same equal rights as all US citizens.

Present Day

We have come a long way to ensure that people with IDD are given the same dignity, rights, and respect deserving of all people. Considering the past 100 years, people with IDD are no longer shuttered away in institutions, cast to the margins of society, and euthanized. Today, they have lawful rights to education, access, and public benefits to assist them in living independently. We celebrate this progress, and still, we still have room to grow. The IDEA lacks funding, which impacts the ability of schools and teachers to support people with IDD. According to a survey from National Public Radio, 82% of special educators across the nation report there are not enough professionals to meet the needs of students with disabilities. Additionally, roughly 11% of special education teachers do not meet the required standards.

The transition from childhood to adulthood can be extremely difficult for people with IDD. Those up to 21 years of age are legally entitled to public education, while those who are 22 and older have ‘aged out’ of the school system. There is a tremendous lack of resources for transition services such as in-school preparatory programs, career services, and work-based learning experiences. This leads to high rates of poverty and unemployment for people with IDD. The 2018 National Core Indicators survey found only 20% of working-age adults supported by state IDD agencies were employed in a paid job in the community, and most of them worked limited hours with very low wages.

Hand-in-hand with the issue of poverty is a housing crisis. Approximately 4.8 million non-institutionalized people with disabilities who rely on federal monthly Supplemental Security Income (SSI) have incomes averaging only about $9,156 per year – low enough to be priced out of every rental housing market in the nation. As affordable housing grows as an issue that is facing more than just people with IDD, people with IDD are made even more vulnerable.

Other current issues people with IDD are facing are a shortage of physicians with skills and adequate training to care for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, resulting in care focused on a particular disability rather than whole-person care. There is a lack of trained and culturally sensitive support staff in healthcare facilities, and there is a scarcity of medical practices willing or prepared to take the time to properly care for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

These are just a few of the present-day issues that we are working to resolve. Advocacy and education are essential to creating further policy and awareness to shift the social tide and make issues facing people with IDD a priority. CPWD is committed to supporting people with disabilities as part of our mission to provide resources, information, and advocacy to assist people with disabilities in overcoming barriers to independent living.