March is Women’s History Month, and March 8th celebrates International Women’s Day. Some of the most influential leaders in the Independent Living Movement have been women, and we at CPWD want to honor the legacy these powerful women have created in shaping society to open their hearts and minds to disability rights. Here is a brief history of just three of the many women leaders that have led this movement to where it is today.

Agatha Tiegel Hanson

Agatha Tiegel Hanson at Gallaudet University

Agatha Tiegel Hanson was born in Pittsburgh in 1873. She lost her hearing and her sight in one eye at age 7 after a case of spinal meningitis. Because she could no longer hear, she found great joy in the rhythms of poetry and went on to become a renowned poet. She studied at the Western Pennsylvania School for the Deaf and went on to be the first woman to graduate with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Gallaudet College as her class valedictorian.

At Gallaudet College, she co-founded the secret society organization for women titled O.W.L.S where the thirteen women students of the college could debate with one another since they were not allowed to debate with the men. She was unanimously voted president. O.W.L.S was later renamed Phi Kappa Zeta sorority. At her graduation, she gave a remarkable speech titled, “The Intellect of Women.”

“Civilization is too far advanced not to acknowledge the justice of woman’s cause. She herself is too strongly impelled by a noble hunger for something better than she has known, too highly inspired by the vista of the glorious future, not to rise with determination and might and move on till all barriers crumble and fall.”

She went on to teach for several years at the Minnesota School for the Deaf and later served as an editor for the Seattle newspaper for the deaf community, The Seattle Observer. She was a prolific writer and published several poetry books. She and her husband were prominent figures in the Seattle Deaf Community and fought tirelessly for the rights of people with disabilities as well as women’s rights. She worked within organizations such as the Puget Sound Association of the Deaf, the Washington State Association of the Deaf, and the deaf mission of the Episcopal Church.

She died in 1959 at age 86 after a long illness. Gallaudet University named the Plaza and Dining Hall after her, established Deaf Women’s Studies courses, and produced “The Feather,” a movie about her life.

Helen Keller

(Credit: Helen Keller, 1952, Jerusalem, Israel courtesy Karl Meyer Mideast Collection, Perkins School for the Blind)

Helen Keller is one of the most well-known activists for disability rights. She was born in 1880, and it was soon discovered, after an illness at 19 months old, that she lost both her sight and hearing. It wasn’t until the age of seven that she began working with her teacher Anne Sullivan, who taught her language, reading, and writing. Keller described the day Sullivan began teaching her as “my soul’s birthday.” She described the moment she realized that the scratches Sullivan was making in her hand were language describing the world around her.

“I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten — a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that w-a-t-e-r meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. The living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, set it free!”

Keller went on to become the first Deafblind graduate of Radcliffe College of Harvard University in 1904. She worked for American Foundation for the Blind from the mid-1920s until her death in 1968, advocating for schools for the blind and braille reading materials. She traveled to 25 different countries championing the rights of deaf and blind people.

As popular as Helen Keller is, most people are unaware of how controversial she was for her time. Not only was she an advocate for

Helen Keller with her teacher Anne Sullivan in 1915 – Getty Images

disability rights, but she was also an outspoken socialist, suffragist (advocating for women’s voting rights), supporter of birth control, pacifist, and supporter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Her controversial views put her on the FBI watchlist as possibly having ties to the communist party.

“I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment. I have learned that the power to rise is not within the reach of everyone,” she wrote, speaking of her horror towards poverty and racism.

Keller wrote 14 books and more than 475 speeches and essays. She met with every US President from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1920, she co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union. She died in 1968 after a series of strokes.

Judith (Judy) Huemann

Judy Huemann. Photo credit Joseph Shapiro/ NPR

Judy Huemann, born in 1948, devoted her life to disability rights activism, both as a protester and grassroots organizer in the 1970s and 80s and as a policymaker serving as Assistant Secretary of Education for Special Education and Rehabilitation Services from 1993-2000. She was integral in expanding the Independent Living Movement internationally and is widely regarded as “the mother of the disability rights movement.”

At the age of 18 months, she contracted polio which left her in a wheelchair. When she was two years old, a doctor tried to convince her parents to leave her in an institution and go on with their lives. Thankfully, they refused.

When Judy was five years old, her mother took her to school to be enrolled. On the way into the school, they were stopped by the principal and told she couldn’t come to school because it wasn’t handicapped-accessible and her wheelchair was a fire hazard. He reassured them that the board of education would send a teacher to their home. The teacher did come, but only for about 2 ½ hours per week. It wasn’t until she was 9 years old, and after a long fight for inclusion by her parents, that she was able to go to school in a school building with other students. Even so, she was only able to be in a class with other kids with disabilities, some up to 21 years old, and completely segregated from the rest of the students, including lunch and recess.

As she continued to high school, she faced accessibility barriers as none of the schools in New York City were wheelchair accessible. Once again, administrators told her parents she should be schooled at home. This time, a coalition of parents with children with disabilities demanded that public high schools in New York be made accessible, and won. Finally, Judy was able to access and attend school as a student. However, she continued to face discrimination due to her disability. In a 1988 speech to Congress, she told a story about being denied receiving an award at school because they wouldn’t allow her to come onto the stage in a wheelchair.

Judy Huemann minored in education at Long Island University with the goal to become a teacher. All the teaching exams she was required to take were in completely inaccessible buildings. Friends had to carry her up and down the stairs on testing days. She passed the oral and written exams, but during the medical exam, the woman administering the exam asked her to show her how she went to the bathroom. She refused, saying if she had to teach kids how to use the bathroom she was able to do that. They didn’t pass her on the medical exam and was denied her teaching license. The reason given was her paralysis. She decided to sue the New York Board of Education on the basis of discrimination.

Her story was covered in the New York Times, The Today show, and many more media outlets. A local newspaper printed an article with the title “You Can Be President, Not Teacher, with Polio.” The judge who presided over her case was the first African American female judge, Constance Baker Motley, who understood discrimination. She ruled in Huemann’s favor. Huemann passed her medical exam and went on to teach at the same elementary school she went to as a child.

Huemann received an outpouring of support from other people with disabilities from all over the country. Due to their response, in 1970, she co-founded the organization Disabled In Action, which focused on securing civil rights protections for people with disabilities through protests. In 1972, President Nixon vetoed the Rehabilitation Act. Huemann and fellow members of Disabled In Action protested, effectively shutting down Madison Avenue. The protest proved successful, and Nixon passed the act.

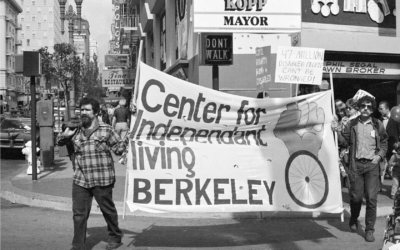

Judy Huemann and other activists at the 504 sit-in protest

In 1975, Huemann was invited to San Francisco by Ed Roberts (considered to be the father of the Independent Living Movement) to be Deputy Director of the Center for Independent Living, where she served until 1982. It was here, in 1977, that she and Kitty Cone organized and led the 504 sit-ins, which we have discussed in previous articles, protesting the refusal of the U.S. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to sign meaningful legislation for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. The protest lasted 28 days, and to date is the longest peaceful sit-in protest in the U.S. The protest was a success, and Section 504 was passed, marking a monumental win for the rights of people with disabilities.

“Disability only becomes a tragedy when society fails to provide the things we need to lead our lives — job opportunities or barrier-free buildings, for example,” she said. “It is not a tragedy to me that I’m living in a wheelchair.”

Judy Huemann went on to serve many roles in the continuous fight for the rights of people with disabilities. She co-founded the World Institute on Disability with Ed Roberts and Joan Leon in 1983, serving as co-director until 1993. From 2002 to 2006, Heumann served as the World Bank Group’s first Advisor on Disability and Development. In 2010, Heumann was appointed by former President Barack Obama as the Special Advisor on International Disability Rights for the U.S. State Department, where she served until 2017. From September 2017 to April 2019, Heumann was a Senior Fellow at the Ford Foundation where she worked to help advance the inclusion of disability in the Foundation’s work.

Judy Huemann passed away on March 5, 2023, at the age of 75 after being hospitalized with breathing problems. Not only will she be remembered and missed by all those whose lives she touched, but her legacy of affecting systemic change in rights for people with disabilities is the bedrock of many of the benefits, freedoms, and rights we have today. Read the statement by President Joe Biden on her passing.